The Future of Port of Churchill: A Potential Rival to Port of Duluth

Plans are underway to develop the Port of Churchill on Hudson Bay to serve container ships and to upgrade the railway line into Western Canada. Such a development has potential to develop competition between Churchill and Port of Duluth on Lake Superior.

Introduction

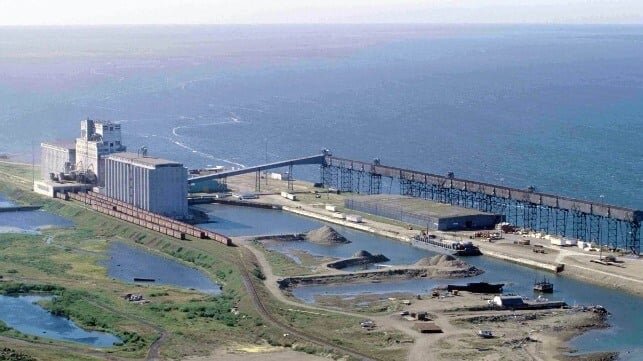

Plans to develop the Port of Churchill on Hudson Bay date back to 1923, and it opened in 1931 following completion of the Hudson Bay Railway line. The port was intended to export Western Canadian agricultural products such as wheat, barley, and oats to England and Europe. At the time, the Canadian navigation canal from Montreal to Lake Ontario could only transit small vessels, some of which had ocean sailing capability. However, much larger vessels could sail into the Port of Churchill, which offered a low-tide water depth of just over 37 feet.

The Port of Churchill remained competitive until the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway during the late 1950s when the largest ocean freight carriers of that era were able to sail inland to the Upper Great Lakes and the grain terminal at Port of Thunder Bay. Compared to Hudson Bay, the St. Lawrence Seaway offered an extended shipping season for ships of equal size, enhancing the competitiveness of the Port of Thunder Bay for transferring grain between railway and ship transport. Traffic through Port of Churchill subsequently decreased until its closure and sale during the late 1990s.

Potential Future

The railway line that extends southwest from Port of Churchill indirectly connects to a population of over 25 million spread across Western Canada and the Northwestern United States. While sailing vessels between the U.S. West Coast and Europe via the Panama Canal occurs regularly, recent drought across the watershed of that canal restricted shipping. Some container traffic between Europe and the northwestern United States may be diverted via Port of Duluth on Lake Superior, using Seawaymax-sized container ships, while other traffic moves to and from East Coast container ports along railway lines approaching peak operational capacity.

An examination of water depths around the Port of Churchill indicates potential to deep-dredge the dock area. Boulders would need to be relocated westward from the sea floor, with some needing to be broken apart using dynamite. Dredging the dock water draft to 52 feet at low tide would allow container ships of 12,000 to 14,000-TEU capacity and a 14-meter draft to berth at the dock. Future occasional dredging may be needed due to silt build up. Future weather conditions would likely allow port operations between early June and early December, coinciding with peak container traffic season.

Railway Connection

A large section of the railway line that extends south and southwest of the Port of Churchill crosses over tundra/muskeg, restricting maximum axle weights for locomotives and wagons/carriages. Container cars would likely have to operate in a single stack configuration. The combination of speed and weight restrictions would require the operation of ballast-reduced locomotives each coupled to a ballast-reduced railway slug unit to which they supply electric power, to drive additional axles and increase low-speed traction. Operation of extended length container trains would require multiple mid-train locomotives (DPU or Distribution Power Units) spread throughout each train.

Such operation would require additional sidings at Port of Churchill. At a point southwest of Port of Churchill where geology allows for operation of higher axle loads, locomotives would be exchanged, and containers re-arranged to double stack configuration. While such operation would increase railway operating costs, the operation of much larger container ships at Port of Churchill would reduce transoceanic per container transportation costs compared to multiple Seawaymax container ships calling at Port of Duluth. Cost competitiveness of shipping containers via Port of Churchill depends on reducing railway transportation costs between the port and Western Canada, as well as the northwestern United States.

Economic Factors

The volume of future container-based trade between Europe and the combination of Western Canada and northwestern United States will determine the viability of container transfers at Port of Churchill. While moving containers via the Panama Canal between Europe and the northwestern USA and Western Canada incurs competitive transportation costs, sending containers via Port of Churchill incurs greatly reduced time-in-transit, allowing for faster delivery schedules and more transatlantic return trips per ship. Railway lines extending to U.S. East Coast and Gulf Coast ports now operate near capacity, raising per container transportation costs along those lines in response to increasing demand for service.

Port of Churchill’s competitive edge involves a portion of customers and shippers being willing to pay higher per container transportation costs in exchange for faster container delivery schedules. While Port of Duluth would be restricted to serving container ships of 1,000-TEU capacity, Port of Churchill following dredging would be able to berth ships of up to 14,000 TEU. The annual cyclical peak of container traffic volumes occurs between July and November when Port of Churchill would be fully operational. Innovation that assures competitive railway transportation costs to and from Port of Churchill container terminal is essential.

Top image: Grain terminal at Port of Churchill (Ansgar Walk / CC BY SA 2.5)

The opinions expressed herein are the author’s and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.