The most expensive ship collisions in the history of maritime are remembered not only for the staggering economic costs and financial ruin they caused, but also for the tragic loss of lives of hundreds or even thousands of people. They are measured not just in terms of the value of the ships but also the costs of salvage operations, the clean-up efforts, legal claims, compensation and the resultant environmental damage.

Most Expensive Ship Collisions & Maritime Law Changes

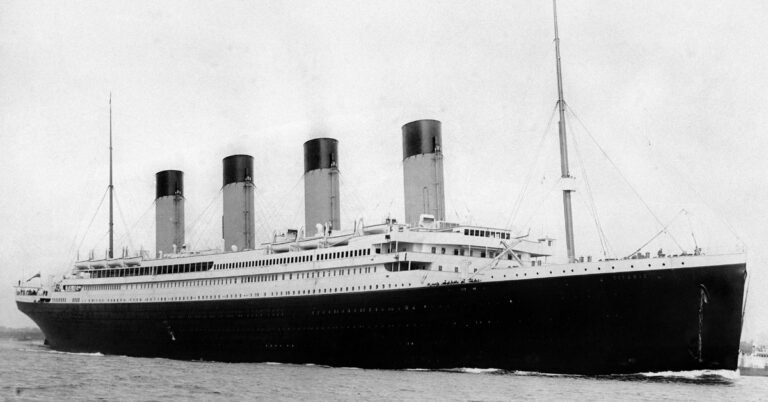

One of the most expensive ship collisions is that of the RMS Titanic. Though the steamship collided with an iceberg and not another ship, the disaster led to tremendous losses.

On April 15, 1912, the Titanic, which was called ‘unsinkable’, struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean during her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York.

It cost $7.5 million to construct in 1912, which is equivalent to approximately $243 billion today, when adjusted for economic impact and inflation.

More than 1500 people died in the incident, and the event has been popularised in the famous movie directed by James Cameron.

The ship had luxurious fittings, cargo and personal belongings of the wealthy who were travelling on it, leading to massive legal and insurance claims.

The disaster also brought new maritime safety laws, the most far-reaching legal outcome being the creation of SOLAS in 1914, which laid down global minimum safety standards for the construction, equipment and operation of merchant vessels. It was revised in 1974 and remains a cornerstone of maritime safety today.

It was now mandatory for ships to carry enough lifeboats for everyone, as the Titanic had lifeboats for just one-third of those onboard. Regular lifeboat drills also became compulsory.

Additionally, as Titanic’s radio distress calls were not answered, laws now required all ships to maintain a 24-hour radio watch and said that radio operators should be licensed, which was codified in the Radio Act of 1912.

The International Ice Patrol was established for monitoring and reporting iceberg locations in the North Atlantic.

Regulations also focused on maintaining higher watertight bulkheads and double hulls.

It was also advised that ships decrease their speed when traversing through ice-filled waters.

With time, maritime law evolved so that the ship owners’ liability was not only limited to the value of the vessel’s remains after a disaster, but instead based on the ship’s tonnage, offering more equitable compensation to the families of victims.

Another one of the most expensive ship collisions ever has to be the Costa Concordia disaster. It happened on January 13, 2012, when Costa Concordia deviated from its Mediterranean route and hit a submerged rock off the coast of Isola del Giglio, Italy.

The total cost, which included compensations, salvage, refloating, towing and scrapping, was estimated to be 2 billion dollars, over three times the vessel’s 612 million dollars construction cost.

32 people lost their lives, and the incident resulted in criminal convictions for the captain and increased scrutiny for cruise ship safety protocols.

SOLAS was amended in 2013 after this incident, and muster drills became mandatory for ships before departure, along with emergency instructions and improvement in life jacket stowage for passengers.

It also introduced mandatory evacuation analyses for non-RORO passenger ships and proposals for double-skin protection in watertight compartments.

The incident led to increased standards for crew training, passenger briefings and emergency equipment on cruise ships.

Another incident is the collision of the passenger ferry Dona Paz with the oil tanker MT Vector on December 20, 1987, in the Tablas Strait, Philippines.

The precise monetary value is not known; however, the cargo of 8800 barrels of oil and gasoline caught fire, and over 4300 people died, leaving only 26 survivors.

The disaster brought to light several regulatory failures, including overcrowding, lack of safety drills and improper crew training.

After this incident, the Philippine Maritime Authority enforced stricter vessel inspections, passenger capacity limits and improved emergency preparedness. It strengthened the national oversight and regulatory enforcement in the Philippines.

The IMO is slowly shifting from prescriptive rules to goal-based standards, allowing for new technologies and ship designs while maintaining the fundamental safety criteria.

SOLAS is also being regularly amended to address emerging risks, like new fuels, automation and alternative propulsion systems.

Major Causes of Ship Collisions

One might think that with advanced maritime technologies and modern ship designs, the risk of collisions has reduced, however, the recent incidents suggest otherwise, as in today’s time, most of these occur due to human error and negligence.

Mistakes made by ship’s crew, such as operating under the influence, ignoring navigation systems, being sleep deprived, inadequately trained, lacking experience, or suffering from fatigue or poor mental health, can contribute to ship collisions or maritime accidents. In addition, malfunctions, engine failure, mechanical issues, equipment breakdowns, bad weather, storms, poor visibility, high winds, or ice can also make navigation challenging.

Failure to follow safety procedures, like the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), or operating an unseaworthy vessel with faulty lighting, lack of radar, or improper maintenance, can lead to collisions. Collisions may also occur when ships strike stationary objects due to miscommunication, faulty infrastructure, inability to heed warnings, or poor decision-making by the ship’s captain.

Increased maritime traffic in busy shipping lanes, combined with high speeds and operational pressures, has raised the risk of collisions. In 2024, there were 251 reported vessel collisions globally, making collisions the second most common type of shipping incident after machinery failure. From 2015 to 2024, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) registered 2,935 maritime accidents involving 3,352 ships.

Recent cases of ship collisions include the collision between container ship MV Solong and oil tanker MV Stena Immaculate in the North Sea. The investigation revealed that neither vessel had a dedicated lookout on the bridge when the collision occurred. The captain of MV Solong was arrested and charged with gross negligence manslaughter. Another case involved the training ship of the Mexican Navy, ARM Cuauhtémoc, colliding with the Brooklyn Bridge in New York due to a mechanical failure, resulting in injuries and fatalities.

It is crucial for ship’s crew to prioritize safety, follow regulations, undergo proper training, and maintain their vessels to prevent collisions and ensure the safety of maritime operations.